Introduction

Despite the emergence of OER, the role of mobile learning, in general, and that of language processing technologies, in particular, has remained largely under-explored in the context of adult foreign language learning. This study sets out to bridge the gap between the possibilities offered by ICTs and the huge demand for ubiquitous personalized language learning opportunities.

This report provides a state of the art review of the use of mobile devices for non-formal learning and in particular adult language learning. It will consider the challenges and opportunities of recognition of learning achievements through open learning. The aim is to inform the debate concerning recognition of open learning and indicate the types of recognition practices in existence, and the factors that influence them. Practices, attitudes and rationales for the types of recognition awarded are discussed, along with the factors that influence decisions and the contexts in which non-formal, open learning are recognised.

This introduction sets the scene for the report in terms of key definitions. Learning can be classified into three main categories: formal learning, informal learning and non-formal learning. Formal learning is learning that occurs in an organised and structured context (e.g.in an education or training institution or on the job) and is explicitly designated as learning (in terms of objectives, time or resources). Formal learning is intentional from the learner’s point of view. It typically leads to validation and certification. In contrast, informal learning is learning resulting from daily activities related to work, family or leisure. It is not organised or structured in terms of objectives, time or learning support. Formal learning is the most socially recognised form entrusted to official institutions with structure learning objectives, a prescribed timeframe and associated support. It is intentional on the learner’s part and leads to certification. Informal learning is mostly unintentional from the learner’s perspective. Informal learning corresponds to everyday life, i.e. activities whose main objective is not educational. It is not structured, it is non intentional and does not lead to certification. Finally, non-formal learning is learning which is embedded in planned activities not always explicitly designated as learning (in terms of learning objectives, learning time or learning support), but which contain an important learning element. Non-formal learning is intentional from the learner’s point of view. In particular, adult non-formal learning refers to the self-directed intentional learning that takes place in people’s leisure time outside of both the workplace and the curriculum of formal learning activities. Non-formal learning is offered by many types of organisations not officially recognised as learning institutions and does not lead to certification. Self-directed informal learning is not completely divorced from the non-formal learning that takes place in adult education provision. Any formal or non-formal learning episode may have informal attributes or qualities because it will help to advance the self-directed informal learning goals of the individual learner.

Accreditation is a process by which an officially approved body, on the basis of assessment of learning outcomes and/or competences according to different purposes and methods, awards qualifications (certificates, diplomas or titles), or grants equivalences, credit units or exemptions, or issues documents such as portfolios of competences. In some cases, the term accreditation applies to the evaluation of the quality of an institution or a programme as a whole. (UNESCO, 2012). In contrast, credentialisation is the award of academic credentials of any sort, by an academic institution, usually on the basis of completed assessment.

Related to these terms is the term competences, which indicate a satisfactory state of knowledge, skills and attitudes and the ability to apply them in a variety of situations. (UNESCO, 2012). A qualification is an official record (certificate, diploma, degree) of learning achievement, which recognises the results of all forms of learning, including the satisfactory performance of a set of related tasks. It can also be a condition that must be met or complied with for an individual to enter or progress in an occupation and/or for further learning. (UNESCO 2012). Validation is the confirmation by an officially approved body that learning outcomes or competences acquired by an individual have been assessed against reference points or standards through pre-defined assessment methodologies (UNESCO, 2012)

Finally, recognition of learning is a process of granting official status to learning outcomes and/or competences, which can lead to the acknowledgement of their value in society (UNESCO 2012).

Learning outcomes are the set of knowledge, skills and/or competences an individual has acquired and/or is able to demonstrate after completion of a learning process. (CEDEFOP, 2009, from the definition of learning outcomes) Learning achievements are similar to learning outcomes, but normally self-initiated by the learner, not pre-defined by a set curriculum.

The term ‘open learning’ is used in a slightly different sense from ‘open education’ in this report. Where ‘open learning’ is used, there is an implication that the learner has agency (or is the implied subject of the sentence), whereas ‘open education’ is used when providers are the stated or implied agents. The rationale here is that it sounds awkward to talk about ‘providers of open learning’, just as it sounds awkward to refer to the ‘recognition of open education achievements’ on the part of learners.

Open educational resources and open educational practices have their antecedents in many areas: the drive towards open sharing of creative works and software through Creative Commons and free- and shareware, the growth of digital repositories for teachers to share their materials under open licences, and the policies of research funding bodies, such as the Research Councils in the UK, for open access to data outputs and the subsequent provision of data services to enable these. Similarly many institutions have found popular success through making lectures available via social media channels such as YouTube and iTunes.

In particular, the growth and popularity of MOOCs has generated a great deal of publicity in recent years. Because of the proliferation and high profile of MOOCs, this form of open education is mentioned extensively in the report.

A recent report by the UK Department for Business Innovation and Skills (2013) observed that the development of massive open online courses (MOOCs) in the Higher Education (HE) sector is reaching a point of maturity, where ‘after a phase of broad experimentation … MOOCs are heading to become a significant and possibly a standard element of credentialed University education’ (Ibid, p.5). According to the report, although credit for completion has not been a major motivation for learners up to this point, ‘there are clear signs that this will change’ (Ibid, 5), and there is an increasing demand for the HE sector to provide ‘flexible pathways to learning and accessible affordable learning’ (Ibid, p.6).

In order for MOOCs, and more broadly, learning through open educational approaches, to have a meaningful impact on learners and society in general, mechanisms therefore need to be developed for learners to obtain formal recognition for their learning achievements. The option to gain this recognition will allow those learners for whom open online is not just a hobby or leisure activity to reap the benefits of their efforts. Formal recognition of non-formal, open learning can fast-track learners through traditional education programmes and enable them to demonstrate their skills and knowledge to employers. The same UK report quotes from Nathan Harden, a US-based journalist specialising in higher education, who predicts that open education will supplant traditional universities by offering education at lower costs, and that devices such as ‘certificates of mastery’ will enable greater flexibility in HE, with employers recruiting based on these certificates (Department for Business Innovation and Skills, 2013, p.61).

There are three main routes for recognition of non-formal, open learning:

- Universities may provide exemption from a course/ module upon receiving evidence of successful completion of a MOOC. Following the traditional model for transfer of credits, this route would only be possible if the MOOC provider was itself accredited (by the relevant national body), the content and bibliography were made available, there was an examination in a physical examination centre, and the learner’s identity was validated. Many subject domains also do not recognise awards of fewer than 5 ECTS credits.

- If the above conditions are not met, a university may agree to exempt a student from attendance on a course, but require the student to take an examination. (In this case it is the exempting university providing the examination, not the MOOC provider.)

- There is a form of CPD available to members of occupational groups in the Netherlands in which learners can be awarded ‘Permanent Credits’ on the basis of a certain number of hours’ or days’ attendance at job-related training courses.[i] In these instances, MOOC providers would only need to estimate the notional training hours the MOOC is equivalent to.

The OpenCred project developed a framework for analysing the recognition of open learning was developed comprising the following four domains:

- Formality of recognition

- Robustness of assessment

- Affordability for learner

- Eligibility for assessment/recognition

The framework can be used to make comparisons between open recognition initiatives by ascribing a numerical value for each domain. Once the values for any given initiative have been determined, a diamond-shaped graph can be produced providing a visual overview of the recognition model for that initiative, with formality of recognition, robustness of assessment, affordability of assessment for learners and eligibility for assessment at each of the four points.

The potential of MOOCs as a means to promote accessibility and affordability for all is constrained by the problem of providing high value for low cost. Formal qualifications require robust assessment; otherwise the value of the qualifications is undermined. In the majority of cases observed, the two are intrinsically linked. Robust assessment requires tutor intervention to assess in-depth learning, as (to date anyway) automated assessment can only judge superficial learning. Tutors cost money, but the ideal of open education is that it is free, and therefore robust assessment does not appear to fit neatly within current business models for MOOCs or open education in general. As a consequence, institutions choose to either (a) pass on the cost to learners, or (b) offer assessment and recognition for free only to students enrolled on their own programmes.

There is a cap on the formality of recognition that is awarded for open learning. Even the highest forms of recognition from amongst our examples were limited to a small number of ECTS credits, or only partial contribution to a formal qualification, in the form of exemption from modules or exams. No-one can yet acquire a diploma or generally accepted certificate from open learning alone. Organisations such as the OERu and the VMPass project are aiming to change that; however, these are both in the early stages and so there are no examples yet of learners having achieved an entire qualification via open learning.

Through a series of interviews with key stakeholders, the OpenCred project found that there are a number of perceptions held by different stakeholders in open education that have a direct impact on the sector’s ability to provide recognition for open learning.

One commonly voiced perception is that online education is still seen as a second-rate form of education, with learners and teachers reporting that online courses will be taken less seriously by employers and other educational institutions. A recent Pearson report[ii] on faculty attitude to IT echoes this. The aspect of online learning that generates the greatest concern when it comes to recognition is assessment. Concerns over validation of the identity of the authors of submitted work are stronger if the student is on an online course than on a face-to-face course, and online proctoring is seen by some as a lesser form of validation than an examination in a physical location.

A second perception is that the value of ECTS credits as a currency is sometimes questioned. In some cases, particularly in the UK, highly robust assessment is provided for open learning, but this does not lead to ECTS credits as would be expected. Some anecdotal evidence was also gathered to indicate that even in countries where ECTS credits are widely accepted, their value might be questioned in the context of open, online learning.

A further perception regards the value of badges. From the evidence gathered in this research, it appears that badges do increase learners’ motivation in many instances.

For open education to lead to social and economic mobility, it needs to be free and allow anyone to access it, while also leading to generally recognised qualifications. That is, it needs to score highly on all four of the framework categories. However, it may be that there is no single model that fits all, and that each type discovered here (and new ones that may arise) will enable educational institutions to more effectively identify what shape of open education they are aiming to develop, and from whose experience they can most usefully draw. One option for institutions to consider would be to offer learners the choice between bearing the cost of assessment themselves and enrolling in a mainstream programme. That would potentially widen the audience of open learners applying for recognition.

Greater clarity of information is needed regarding exactly what the MOOC or open learning initiative is offering learners, and what will be required in terms of fees and assessment commitments, should they wish to obtain recognition. Sample certificates are also very helpful in illustrating exactly what credential learners will receive. To be easily recognised by other institutions or employers, the certificates themselves also need to contain detailed information on the nature of the course and the nature of the assessment process.

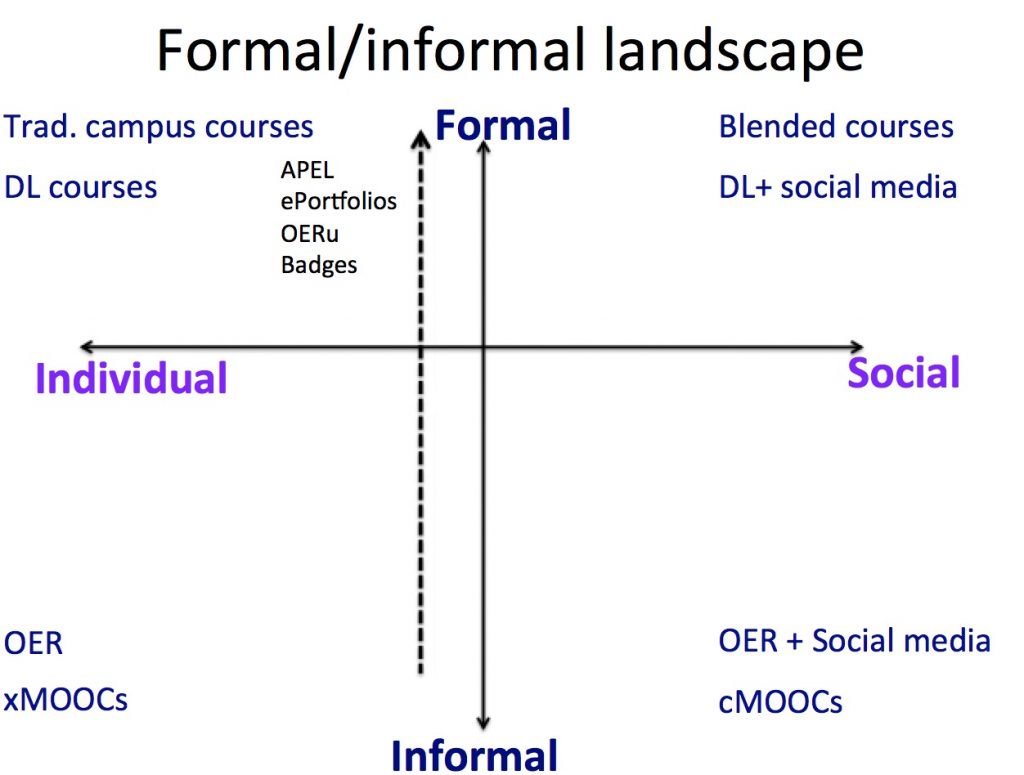

Figure 1 shows the forms of formal and informal learning. Traditional campus-bases courses and distance learning courses sit in the top left quadrant. Adding a social dimension results in blended courses and distance learning courses with social media. Use of Open Educational Resources and Massive Open Online courses sit in the lower left hand quadrant where learners are learning informally on their own. Adding a social dimension results in OER plus social media and cMOOCs. It is possible to convert from informal to formal learning via a number of routes: Accreditation of Prior Learning (APEL), demonstration of achievement of learning outcomes through an e-portfolio, accreditation through organisations like the OERu and through awarding of digital badges.

Figure 1: The formal/informal landscape

Mobile learning

Smart phones and tablets are now practically ubiquitous, and we have practically near ubiquitous wifi connectivity. They are now much more affordble, robust, light and with a good battery life. There is a range of excellent Apps available to support communication, productivity, curation and learning. The positive aspects of these mobile devices are that they mean learning anywhere, anytime is now a reality, more and more websites are mobile ready, learning is possible across contexts and devices. The negative aspects are that being online all the time means that there is no ‘down time’; people are expected to be online 24/7. We are increasingly dependent on these devices and more and more of our data is stored in the cloud.[1] Finally many learners and teachers lack the necessary digital literacy skills to make effective use of these devices for learning purposes.

The field of mobile learning research has matured since its nascent beginnings, and now there are numerous sub-fields: seamless learning, cross-contextual learning,[2] BYOD in the classroom, field-trip learning, ubiquitous learning, wearable learning, evaluation of learning on the move, and mobile devices for data capture to name just a few.

The first generation of mobile devices emerged in the mid-nineties, with the promise of enabling learning anywhere, anytime (Sharples, Corlett et al. 2002). Mobile devices have advanced significantly since this time, nonetheless it is worth referring back to Kukulska-Hulme and Traxler’s (2005) statement of the nature of the initial generation of mobile devices:

What is new in ‘mobile learning’ comes from the possibilities opened up by portable, lightweight devices that are sometimes small enough to fit in a pocket or in the palm of one’s hand. Typical examples are mobile phones (also called cellphones or handphones), smartphones, palmtops and handheld computers (Personal Digital Assistant or PDAs), Tablet PCs, laptop computers and personal media players can also fall within its scope.

Sharples and Pea (2014) provide a useful summary of the key developments in mobile learning; starting with the vision for the creation of Dynabooks in the early seventies. They described a number of key mobile learning projects, which explored learning across different learning contexts (informal and formal), different devices, and different locations. They list Wong and Looi’s (2011) ten characteristics of mobile-assisted seamless learning:

- Encompassing formal and informal learning

- Encompassing personalised and social learning

- Across time

- Across locations

- Ubiquitous access to learning resources

- Encompassing physical and digital objects

- Combined use of multiple device types

- Seamless switching between multiple learning tasks

- Knowledge synthesis

- Encompassing multiple pedagogical or learning activity models.

Sharples and Pea argue that the teacher’s role is still crucial, but that they are more of a learning facilitator, rather than content provider. The projects they describe indicate that with mobile devices it is possible:

To connect learning in and out of the classroom using mobile devices to orchestrate the learning, deliver contextually relevant resources and exploit mobile devices as inquiry toolkits.

They conclude by stating:

Mobile learning takes for granted that learners are continually on the move. We learn across space, taking ideas and learning resources gained in one location and applying them in another, with multiple purposes, multiple facets of identity. We learn across time, by revisiting knowledge that was gained from earlier in a different learning context. We move from topic to topic, managing a range of personal learning projects, rather than following a single curriculum. We also move in and out of engagement with technology, for example as we enter and leave phone coverage.

Bird[1] undertook an evaluation of the use of iPads by Medical students at Leicester University. Overall the students were very positive about the use of their iPads, stating they were convenient, efficient, useful and easy to use. Bird lists the follow as examples of how the students were using the mobile devices for learning:

- To annotate and organised notes

- For group work and development

- Memorising key concepts, through student generated flashcards and quizzes

- For handwriting and drawing

With the increase in access to information and production of knowledge, mobile learning is challenging traditional educational institutions and associated authorities. It provides the opportunity to shift away from teacher-centred pedagogies to an increased focus on learning and the learner, through concepts like the flipped classroom. Because mobile devices enable learning anywhere, anytime and because they can be personalised they are ideally suited to informal and contextual learning. Learning across formal and informal contexts means that there is a blurring of the boundaries between learning and work.

An EDUCAUSE report argues that microlearning encourages learners to focus on discrete chunks of content and learning activities.[2] Fastcodesign[3] argues that there are ten ways in which mobile learning will revolutionise education:

- Continuous learning: learning is increasingly getting interspersed with our daily lives through the use of mobile devices and near ubiquitous access to the Internet.

- Educational leapfrogging: low cost mobile devices are particularly important in developing countries.

- A new crop of older, lifelong learners: often referred to as the silver surfers, are increasingly getting into using mobile devices, often motivated by a desire to keep in touch with their children and grandchildren via social media.

- Breaking gender barriers: in parts of the world where woman are not allowed access to formal education, mobile devices provide them with a means to access high quality resources and to communicate with peers.

- A new literacy is emerging: there are now numerous companies (such as Codeacademy) that teach people via interactive lessons to write software programmes.

- Education’s long tail: The vast array of resources to support many different subjects means that mobile devices enable learners to study niche subjects.

- Teachers and pupils trade roles: Learning and teaching becomes a two way process, where teachers can learn from the learners and vice versa.

- Synergies with mobile banking and mobile health: A lot can be learnt from the way in which mobile banking and health have developed, such as using text messaging to deliver short lessons, and give teacher feedback and grades.

- New opportunities for traditional educational institutions: Mobile learning can potentially complement and extend traditional educational offerings. We are seeing a disaggregation of formal education. Increasingly rather than signing up for a full course, learners may instead choose to pay for components, such as access to high quality resources, pedagogically informed learning pathways, support from tutors or peers, and accreditation.

- A revolution leading to customised education: Mobile learning is not just about digitising existing content, it is about harnessing the power of social media and embracing open practices.

Te@chthought[4] lists the following 12 principles of mobile learning:

- Access: in terms of access to content, peers, experts, and resources.

- Metrics: increasing there are metrics associated with how we are using mobile devices, which can be used to inform and improve the way we learn.

- Cloud computing: means that we can access information anywhere, via any device.

- Transparent: transparency is a byproduct of connectivity, mobility and collaboration.

- Play: is a key characteristic of authentic, progressive learning. In a mobile learning environment, learners encounter a dynamic and often unplanned set of data, domains and collaborations.

- Asynchronous: enabling a learning experience that is personalised, just in time and reflective.

- Self-actuated: where learners plan how and what they learn, facilitated by teachers, who are the experts in terms of the resources and assessment.

- Diverse: learning environments are constantly changing, enabling learners to encounter a stream of new ideas, unexpected challenges, and constant opportunities for revision and application of thinking.

- Curation: there are now a wealth of Apps to support curation so that individual learners can group and share useful resources.

- Blending: Across the physical and digital space and across different devices, supporting both formal and informal learning.

- Always-on: Always-on learning is self-actuated, spontaneous, iterative and recursive.

- Authentic: enabling situative and personalised learning.

So it would appear that mobile learning has finally come of age, it will be interesting to see how the use of mobile devices learning and teaching develops in the coming years.

The role of mobile learning in adult language learning

This section considers the role of mobile learning in adult language learning. It examines the current landscape of adult non-formal learning using digital technologies. It describes how adult are using technologies for non-formal learning and reviews the associated tools, resources and services used to support this. The intention is to develop a shared understanding of the ways in which digital technologies are used for adult non-formal learning and how this could be enhanced to transform adult non-formal learning in the future.

Mobile learning as a research field has expanded in the last ten years or so, particularly in light of the emergence of smart phones, mobile devices and e-books. Work in the field has shown how mobile technology can offer new opportunities for learning that extends beyond the traditional teacher-led classroom. Mobile learning is not just about learning using portable devices, but also about learning across contexts.

The meaning of the term mobility (See Traxler in Bachmair 2010 pp 103 – 113) in as in mobile learning or more specifically mobile assisted language learning has evolved over time. Mobility often refers to the mobile device, technology, system or access via a portable, handheld, personal electronic device often connected to the network, enabling anywhere, anytime access to data, ICT tools and web 2.0 applications. Mobility also refers to time and place. Sharples (2006) defines m-learning as:

The processes of coming to know through conversations across multiple contexts amongst people and personal interactive technologies.

The key characteristics of mobile learning include:

- Enables knowledge building by learners in different contexts.

- Enables learners to construct understandings.

- Mobile technology often changes the pattern of learning/work activity.

- The context of mobile learning is about more than time and space.

Mobile learning can be motivational in a number of respects: it can facilitate personal control, it invites ownership it can be fun, it can promote communication, it can enable learning in context, it can provide continuity between contexts.

Adult non-formal learning is important in a number of respects. Firstly, it is an important and valuable part of an individual’s learning journey. Secondly, it can help us respond to the challenges of a changing society. Thirdly, it can support both individual happiness and motivation and well-being and social cohesion and inclusion. For these reasons it deserves substantial attention from adult educational practitioners, researchers, policy makers, those involved in the technology industry and the adult learners themselves. Indeed there is growing policy interest in adult non-formal learning.

A recent report (Hague and Logan 2009) identified the following from a survey on adult non-formal learning:

- Adult non-formal learning is extensive, with 94 % of adults having engaged in some form of non-formal learning activities over the previous three months.

- 79% of adults say they use technology for learning in their leisure time and adults use technology for this purpose for an average of eight and a half hours a week.

- 96% of those who use technologies to learn in their leisure time do so at home.

- Adults use a wide variety of technologies to learn, with the Internet, TV, DVDs and videos being the most common.

- 75% of adults were able to cite at least one benefit of using technologies for non-formal learning, whilst 23% were unable to cite any benefits.

- 47% of respondents did not think that there were any factors preventing them from using technologies to learn informally, whilst 44% cited at least one barrier.

Promoting adult informal and non-formal learning is important as a means to respond to the many changes and challenges facing society today. These include: operating in an uncertain economic climate, adapting to globalisation and climate change, working in a context of rapid technological change, moving from an industrial to an information or knowledge-based economy, and dealing with increasingly complex career patterns. These factors will mean that there is an increase in the number of learners in the future and these learners have changing learning priorities. Adult learning can enable people to find meaning and purpose in periods of unemployment and in post-employment. It can give them transferable skills to help them make career changes. Finally, it can provide a way to share knowledge and experience between generations. Adult informal and non-formal learning enable learners to set their own learning goals, in a way that is personally meaningful within their own lives and contexts.

Digital technology can facilitate adult learning in a number of ways:

- It can provide access to information about a wide range of learning opportunities.

- It can inspire interest in a particular subject.

- It can provide opportunities and resources for adult learner to continue learning after they have finished a particular formal course, leading to lifelong learning.

- It can widen accessibility to learning by offering alternative pedagogical approaches.

- It can open up interaction and collaboration between adult learners in dispersed geographical locations.

- It can transform the way people learn by allowing innovative and collaborative learning practices.

- It can provide opportunities for adults to reflect on their learning.

- It can increase the options and resources available to adult education providers.

- It can help to engage the adult learners of the future.

- It can allow adults to engage in learning which suits their learning needs and takes place at their own pace.

- It can offer a convenient, flexible and engaging learning medium.

Technologies can be used to make connections more visible between non-formal learning and the informal self-directed learning that takes place at home or in locations outside adult educational settings. They can also be used to support learners in their learning journey and make them more away of it. Finally, they can be used as a learning medium and deliver mechanism for adult education provision.

However, it is important to note that the benefits of using technology for learning are not determiner by the technology itself, but derive from the manner in which the technology is used, the opportunities the technology offers for the development of new learning practice, and the context within which learning takes place. One of the challenges with using technology for learning is to consider how they can be used to facilitate a deeper sense of learning, which does not rely simply on the transmission of information. The focus needs to be on using them in new and transformative ways to construct not only digital tools and texts, but also to facilitate the collaborative constitution of meaning and the acquisition of new and changed knowledge and attitudes.

Mobile assisted language learning is the learning of a foreign language with the assistance of mobile devices and is a relatively new research area (Vavoula and Sharples 2008).

In a study on the use of mobile devices for language learning, Chen observed the following findings (Chen 2013). Simply providing the students with a mobile device did not result in its effect use in language learning. He concluded that learners need to be properly guided both technically and methodologically. Some students may lack the necessary knowledge and experience to enable them to solve problems in the process of adopting new technologies. Instructional guidance on how the mobile technology can be better use for language learning in terms of activity design and collaboration is important. He did however fin that students’ attitudes towards the usability, effectiveness and satisfaction of mobile devices as tools for Mobile assisted language learning were quite positive. He concluded that mobile devices are ideal tools to foster learner autonomy and ubiquitous learning in informal settings, provided that their technological affordances are clearly articulated to the students.

Conclusion

The report has provided an up to date state of the art review of the use of mobile devices for adult non-formal learning for language acquisition. Key terms were defined and the broad literature on mobile learning and in particular language acquisition were described. It is clear that adult non-formal learning is increasingly important in today’s complex society. New mobile devices, along with near ubiquitous connectivity, means the learning anywhere, anytime is now a reality.

References

Kukulska-Hulme, A. and J. Traxler (2005). Mobile learning – a handbook for educators and trainers. Abingdon, Routledge.

Sharples, M., D. Corlett and O. Westmancott (2002). “The design and implementation of a mobile learning resource.”Personal and ubiquitous computing 6: 220-234.

Sharples, M. and R. Pea (2014). Mobile Learning. The Cambridge Handbook of Learning Sciences. R. K. Sawyer. New York, NY, Cambridge University Press.

Wong, L. H. and C. K. Looi (2011). “What seams do we remove in mobile-assisted seamless learning? A critical review of the literature.” Computers and Education 57(4): 2364 – 2381.

Bachmair, B. (2010). Medienbildung in neuen Kulturraumne. Wiesbaden, Germany, VS-Verlag fur Sozialwissenschaft.

Chen, X. (2013). “Tablers for informal language learning: student usage and attitudes.” Language Learning and Technology 17(1): 20 – 36.

Hague, C. and A. Logan (2009). A review of the current landscape of adult informal learning using digital technologies. Bristol, Futurelab.

Sharples, M. (2006). “Big issues in mobile learning – report of a workshop by the Kaleidoscope network of excellent mobile learning initiative.”

Vavoula, G. and M. Sharples (2008). Challenging in evaluating mobile learning. In Proceedings of MLearn 2008, 8 -10 October, Wolverhampton.

[1] http://www.slideshare.net/tbirdcymru/building-a-digital-platform-ipads-in-undergraduate-medicine

[2] http://www.educause.edu/library/resources/7-things-you-should-read-about-microlearning-mobile-and-flipped-contexts

[3] http://www.fastcodesign.com/1669896/10-ways-that-mobile-learning-will-revolutionize-education

[4] http://www.teachthought.com/technology/12-principles-of-mobile-learning/

[1] See http://e4innovation.com/?p=893

[2] See http://e4innovation.com/?p=879

[i] Similar CPD requirements were found in cases in other EU Member States (for example in Italy, where the government established a framework for validation of vocational competences in 2001 (Cedefop 2007). Within this framework, teacher trainers who have five years of experience can apply for University of Rome training credits by making a personal statement based on their work experience as trainers. Examples from the UK (Scottish Borders College and ACCA) are discussed as case studies in Section 4).

[ii] https://commission.fiu.edu/helpful-documents/online-education/12-ihe-survey-faculty-attitudes-on-technology-2013.pdf